Academic Review

See why academic research recommends the games approach

‘Traditional Formats’ that teach skills through direct transfer from coach to player are mechanical, complicated and linear in nature [22]. Players become conditioned by ‘sayings’ such as “Never play the ball across the back”, so recognize only danger and avoid risk. Consequently, players are disconnected from the realities of the game without context to apply realistic responses [22, 27]. Developing better players requires managing risk by exploring multiple solutions. Learning when to play the ball across the back helps to change the angle of play, maintains possession and decreases predictability. By encouraging players to learn for themselves they become empowered to take control.

Traditional Formats

The following ‘Traditional Formats’ all have fundamental drawbacks:

a) Fixed practices (commonly ‘drills’) repeat technique to refine and reproduce consistently, but control players’ response by limiting options. Skills are broken-down into small steps using a progressive sequence from simple to complex [35], without regard for the complexities of the game environment. Whilst drills are necessary in the army, soccer has more room for expression and individuality.

b) Variable practices extend ‘drills’ by offering alternative directions to adapt technique in, rather than in response to an opponent. Both fixed and variable practices have potential for competition, but this is often limited to 1v1’s/2v2’s.

c.1) Integrated practices: full/small-sided matches. Whilst full competition is engaging, it’s a large step forward from variable practices as players move abruptly from no/limited pressure to full pressure.

c.2) Functional Practices and Phases of Play are used by more experienced coaches to isolate match scenarios towards one main goal. The team defending this goal has little incentive to score so unrealistically retains defensive shape when in possession.

The Stop/Start Approach

The ‘Coaches in Game’ format coaches team play by identifying a ’fault’ before 1) freezing play, 2) asking questions and correcting the fault, 3) demonstrating the ‘correct’ way, 4) rehearsing the ‘correct’ way and 5) restarting play [25]. Whilst painting an accurate picture of specific situations, it removes players’ responsibility, and encourages dependence on the coach.

Coaching “fixed” solutions limits the tools in each player’s armory, leaving them vulnerable to unique or nuanced scenarios. They might know the ‘correct’ way but can’t adapt when this doesn’t work. E.g. the coach tells their ‘Wing Back’ to always guide their opponent towards the touchline. However, if the opposition winger always outpaces them or only threatens from crosses they must adapt.

Instead, guide players to adapt to unique situations by experimenting with different scenarios to discover solutions themselves. Experimentation allows players to understand why it won't work and when there are exceptions, so understanding is more complete, rather than just a remembered rule.

The 'Games Approach'

The ‘Games Approach’ allows experimentation through small-sided games with various conditions, triggering techniques and skills under realistic pressure [33]. First developed in Europe through Deleplace [7] and Mahlo [23], The ‘Games Approach’ was highlighted in the U.K. when Bunker & Thorpe [3] proposed the ‘Teaching Games for Understanding’ model. Several Game-Based Approaches have since emerged, all with slight variations [14].

“Game Sense” [2] took a considerable step forward by encouraging coaches to become facilitators by asking questions that stimulate tactical thinking, rather than just dictating [15, 16, 18]. As facilitator, the coach guides players to find personal solutions to game situations they meet. Questions aren’t asked to find correct answers, but to stimulate thinking as there is no single solution [5].

Light [19] suggested the coach encourage players to take risks, be creative and engage in active learning. Ideally the coach facilitates by using questioning to promote player dialogue and reflection [6, 20, 31], allowing players to be actively involved in their learning through problem solving [26], where they draw on prior experience and knowledge to make sense of learning experiences [21]. The coach can nudge players in a more fruitful direction when they’re way off the mark.

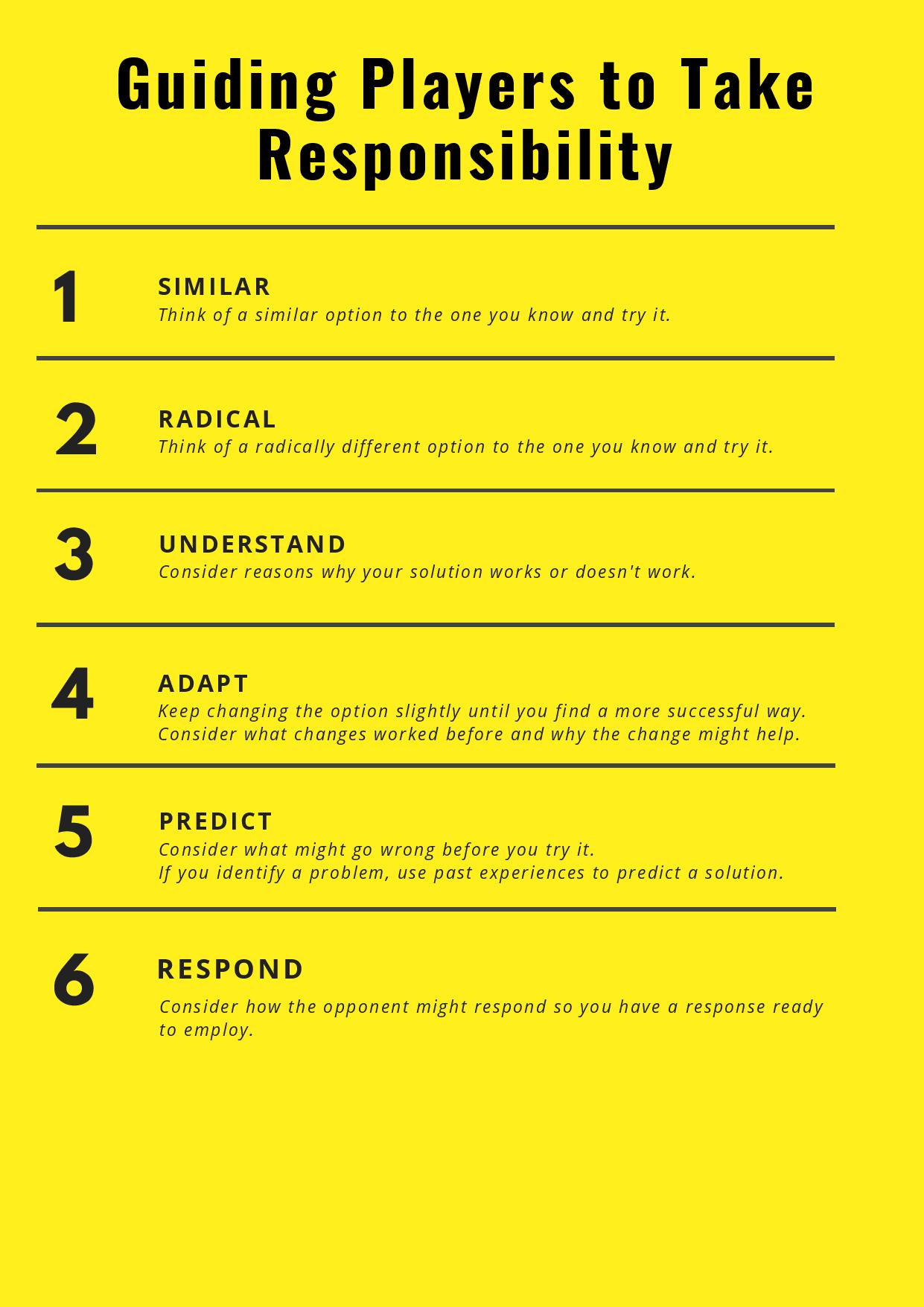

The modern approach to facilitation prompts players to discuss and debate aspects of the game before returning to the game to act upon points of discussion [17]. Initially players are dependent on the coach and struggle to think of new ideas. ‘Figure 2’ helps stimulate players to problem solve independently.

‘Progressive Games’ assist independence by subtly guiding players, whilst empowering them to discover solutions through trial and error. The ‘Games Approach’ focuses on a particular skill/tactic within a realistic environment so that players become comfortable responding to the opposition, rather than a command.

Experts agree on 'Games Approach' benefits

Most ‘Conditioned Games’ mirror a soccer game’s format and rules, keeping players within their comfort zone. Instead, ‘Progressive Games’ take players outside their comfort zone, where they can no longer rely on old solutions, so must think dynamically to succeed. Players gradually become comfortable when challenged by new situations. They learn a wider variety of solutions that can be referenced in tricky and unique match situations.

Several studies identified the design of games as vital [8, 13, 28, 29, 30, 34]. Yet seemingly logical ‘conditions’ often have an opposite effect to the intention. E.g. whilst the intention of the “Maximum 2-touch” condition is to speed up play, players often respond by stopping the ball, so not to rush their second touch. The resultant static ball slows down and makes play predictable. Instead, the ‘Progressive Game’ “Changing Directional Focus” (Figure 4) guides players to speed up play organically by instantly rewarding fast passing.

However, this is challenging when players offer solutions that contradict the coach. Rather than dismiss them, allow players time to experiment to find personalized solutions to overcome danger. It requires a brave, coach to allow players more responsibility, but gains respect and creates more complete players.

Transferring this approach into matches is challenging when a fear of losing leads to a more conservative approach. Instead, competitive matches can be presented as an extension of ‘Soccer Practice’ by combining freedom to explore with the challenge of different opposition. A ‘Progressive Warm Up’ before matches bridges the gap to training.

Barriers to Progress

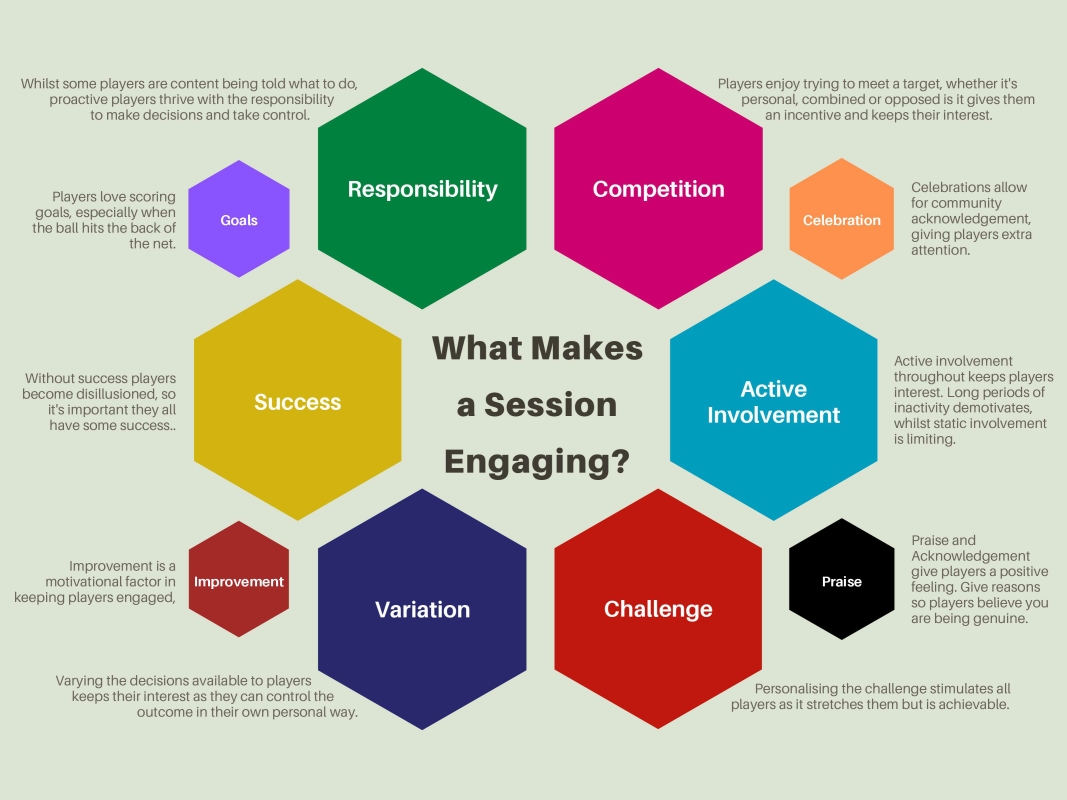

a) Challenge

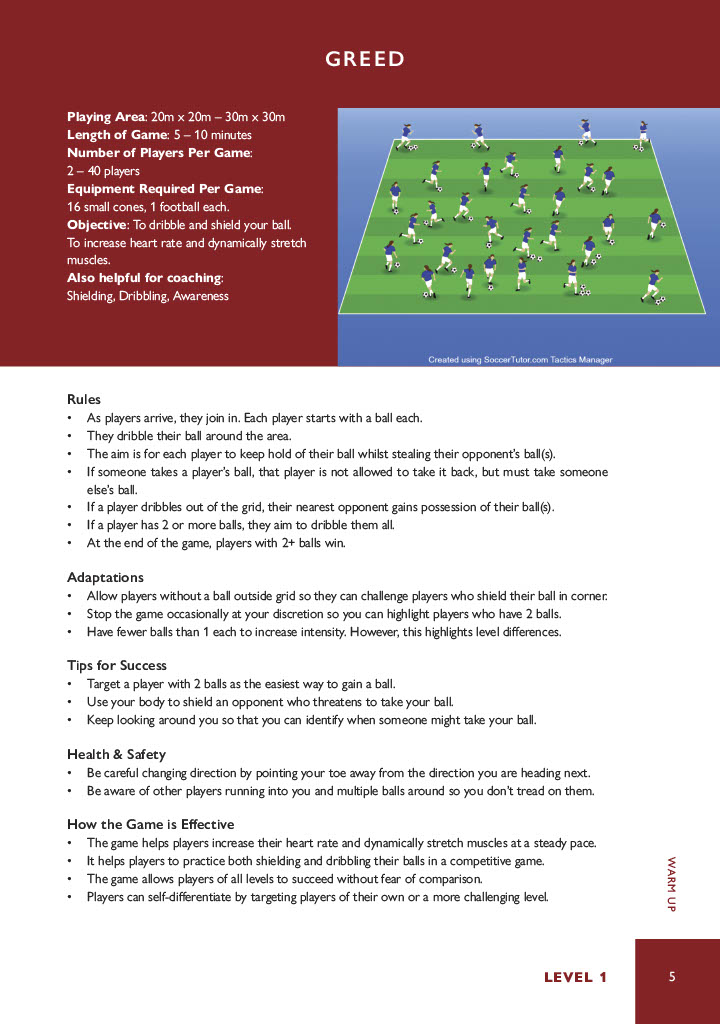

Allow players personalized challenge. Some games e.g. ‘Greed’ (Figure 7) have layers of challenge so that when players succeed, they meet a higher challenge. However, some games are enhanced by players adapting their personal challenge.

Result-based personalization should be avoided though (e.g. First to 5 goals, player ‘A’ has a 3 goal head start). As each player’s challenge within each play is unchanged, the weaker player is over challenged whilst the stronger player is under challenged. It’s sometimes beneficial to compete against much stronger players, but when overdone, players will prioritize 'safe' options to avoid failure.

b) Responsibility

Games encourage experimentation to solve unique game problems. To maximize this, subtly guide players by occasionally offering alternatives, rather than dictating. Use drinks breaks to discuss new solutions so players have time to consider the problem. It’s important they sometimes try out bad/risky solutions so learning is organic, rather than copied.

c) Success

Comparison can demotivate players who regularly lose. Many players see success as ‘winning’, which is less realistic when better opponents are also improving. Instead, measure success based on progress rather than comparison.

d) Variation

A variety of different games, cater for different learning styles and give players opportunity to relate skills to unique situations. Learning is more permanent when players develop understanding through a fuller range of experiences.

e) Active Involvement

High intensity games improve fitness without players realizing they're working so hard. To maximize involvement and intensity:

· Use games rather than drills. Games contain more incentives, so players work harder,

· Prioritize high intensity, competitive games,

· Set up a warm up game that players join in with on arrival to maximize activity.

· Always have the next game already set up so players can start quickly,

· Have recurring games each session to reduce explaining time and maintain intensity,

· Initially have shorter length games to maintain a high intensity. Once players can maintain

the intensity, gradually increase game length to extend.

· Have drinks close by and limit length of breaks to challenge recovery (initially have

slightly longer breaks to build success) and expect players to jog to and from drinks break.

· Play smaller-sided games to increase ball-touches and maximize intensity,

· Limit stopping the practice to coach. Instead, use drinks breaks for feedback,

· Place spare balls spread around the perimeter to restart games immediately,

· Coach holds extra balls in their hands, to restart play.

f) Competition

Use competition effectively to maximize realism and engagement by:

· Emphasizing all player's responsibility to improve rather than beat each other,

· Assist players to set personal conditions as the main challenge, alongside their

opponent (see ‘Adaptations’ section for each game),

· Coaching players to feedback to each other after each 1v1/2v2 challenge to highlight

process, over the result. This includes both praise and advice,

· Creating an environment where competition is prioritized over counting,

· Avoiding recording or announcing scores and prioritizing games without counting.

References

1. Ashraf, O. (2017). Effects of teaching games for understanding on tactical awareness and decision making in soccer

for college students. Science, Movement and Health, 17, 170-176.

2. Australian Sports Commission. (1991). Sport for young Australians: Widening the gateways to participation. Belconnen,

ACT: Australian Sports Commission.

3. Bunker, D. & Thorpe, R. (1982). A model for the teaching of games in secondary schools. Bulletin of physical education,

18(1), 5-8.

4. Chatzopoulos, D., Drakou, A., Kotzamanidou, M. & Tsorbatzoudis, H. (2006). Girls’ soccer performance and motivation:

Games vs technique approach. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 103, 463-470.

5. Chen, S. & Light, R. (2006). ‘I thought I’d hate cricket but I love it!’ Year 6 students responses to Game Sense pedagogy.

Change: Transformations in Education. 9(1), 49-58.

6. Cushion, C. (2013), Applying game centered approaches in coaching: A critical analysis of the ‘dilemmas of practice’

impacting change. Sports Coaching Review, 2, 61-76.

7. Deleplace, R. (1979). Rugby de movement – Rugby total, Paris Review: Education Physique et Sports.

8. Evans, J.R., (2006). Elite level rugby coaches interpretation and use of games sense. Asian Journal of Exercise & Sports

Science, 3(1), 17-24.

9. Evans, J.R. & Light, R.L. (2007). Coach development through collaborative action research – A rugby coach’s

implementation of Game Sense pedagogy. Asian Journal of Exercise and Sport Science, 4(1), 489-499.

10. Gray, S. & Sproule, J. (2011). Developing pupils’ performance in team invasion games. Physical Education and Sport

Pedagogy. 16, 15-32.

11. Griffin, L.L., Mitchell, S.A. & Oslin, J.L. (1997). Teaching Sport Concepts and Skills: A Tactical 'Games Approach', Human

Kinetics, Champaign, Illinois.

12. Guijarro-Romero, S., Mayorga-Vega, D. & Viciana, J. (2018). Aprendizaje tactico en deportes de invasion en la educacion

fisica: Influencia del nivel inicial de los estudiantes. Movimento, 24, 889-902.

13. Harvey, S., Cushion C. & Massa-Gonzalez, A.N. (2010). Learning a new method: Teaching games for understanding in the

coaches’ eyes. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 15, 361-382.

14. Harvey, S. & Jarrett, K. (2014). A review of the game-centered approaches to teaching and coaching literature since

2006. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 11, 101-118.

15. Kidman, L. (2001). Developing decision makers: An empowerment approach to coaching. New Zealand: Innovative Print

Communications Ltd.

16. Kidman, L. (2005). Athlete-Centered Coaching. Christchurch, New Zealand: Innovative Print Communications Ltd.

17. Kinnerk, P, Harvey, S., MacDonncha, C. & Lyons M. (2018). A Review of the Game-Based Approaches to Coaching Literature

in Competitive Team Sport Settings. Quest Illinois – National Association for Physical Education in Higher Education, 70(4),

401-418.

18. Light, R. (2005). Making sense of chaos: Australian coaches talk about game sense. In L. L. Griffin & J. Butler (Eds.),

Teaching Games for Understanding: Theory, research, and practices (pp. 169-181). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

19. Light, R.L. (2013). Game sense: Pedagogy for performance, participation and enjoyment, New York, NY, Routledge

20. Light, R.L. & Evans, J.R. (2010). The impact of game sense pedagogy on Australian rugby coaches’ practice: A question of

pedagogy. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 15, 103-115.

21. Light, R.L. & Georgakis, S. (2007). The effect of game sense pedagogy on primary school pre-service Teachers’ attitudes to

teaching physical education. Australian Council for Health, Physical Education and Recreation Healthy Lifestyles Journal.

54(1), 24-28.

22. Light, R., Harvey. S., & Mouchet, A., (2014) Improving ‘at-action’ decision-making in team sports through a holistic

coaching approach, Sport, Education and Society, 19:3, 258-275.

23. Mahlo, F. (1969). Tactical Action in play. Paris: Vigot Freres.

24. Morales-Belando, M.T. and Arias-Estero, J.L. (2017). Effect of Teaching Races for Understanding in Youth Sailing on

Performance, Knowledge and Adherence. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 88(4), 513-523.

25. National Soccer Coaches Association of America (2011). Coaching Academy. Coaches Teach Players, We Teach Coaches.

Handbook for National Coaching Diploma in Summer 2011.

26. Ollis, S. & Sproulle, J. (2007). Constructivist coaching and expertise development as action research. International Journal

of Sports Science & Coaching, 2, 1-14.

27. Pill, S. (2014), Informing game sense pedagogy with constraints led theory for coaching in Australian football. Sports

Coaching Review, 3, 46-62.

28. Pill, S. (2015). Using appreciative enquiry to explore Australian football coaches’ experience with game sense coaching.

Sport, Education and Society, 20, 799-818.

29. Pill, S. (2016). Implementing game sense coaching approach in Australian football through Action Research. Agora for

Physical Education and Sport, 18(1), 1-19.

30. Praxedes, A., Moreno, A. Sevil, J., Garcia Gonzalez, L. & Del Villar, F. (2016). A preliminary study of the effects of a

comprehensive teaching programme, based on questioning, to improve tactical actions in young footballers. Perceptual &

Motor Skills, 122, 742-756.

31. Roberts, S.J. (2011). Teaching Games For Understanding: The difficulties and challenges experienced by participation

cricket coaches. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 16, 33-48.

32. Robles, M.T.A., Collado-Mateo, D., Fernandez-Espinola, C., Viera, E.C. & Fuentes-Guerra, F.J.G. (2020). Effects of Teaching

Games on Decision Making and Skill Execution: A systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 505

33. Thembelihle, G & Timothy, G.K. (2018). Adopting Game Sense approach to teaching and coaching of sports in Zimbabwe.

European Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science, 4(3), 129-140.

34. Thomas, G., Morgan, K. & Mesquita, I. (2013). Examining the Implementation of a Teaching Games For Understanding

approach in junior rugby using a reflective practice design. Sports Coaching Review, 2, 49-60.

35. Webb, P. and Thompson, C. (2000). Developing thinking players: Game sense in coaching and teaching. Belconnen,

Australia: Australian Coaching Council.